Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: Open the gate Let the sugar run Let the small suns keep burning on Carry the night's last heat inside so that it can stay so that it can stay alive.

Hold that signal steady and true.

[00:00:20] Speaker B: Welcome to Bass by Bass, the paper cast that brings genomics to you wherever you are. Thanks for listening and don't forget to follow and rate us in your podcast. Appreciate.

[00:00:28] Speaker C: Today we have a story that really changes how we look at certain types of blindness. It plays out like a disaster movie, but on a cellular level.

[00:00:37] Speaker B: I do love a high stakes story.

[00:00:39] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:00:39] Speaker B: And to set the stage, I want you to imagine something that feels less like biology and more like, I don't know, economics or even warfare. Imagine a city under siege.

[00:00:49] Speaker C: Okay, I'm with you.

[00:00:50] Speaker B: The supply lines are cut, the food stops coming in. And in this city, you have your essential workers, the ones keeping everything running. And then you have the support staff, the logistics team.

[00:01:00] Speaker C: Right, and when the food runs out, that logistics team has a choice to make. A really tough one.

[00:01:05] Speaker B: Exactly. Do they share what little they have left, or does survival mode kick in? You know, do they just raid the pantry and lock the doors?

[00:01:11] Speaker C: It's a grim thought, but biologically, that's pretty much what happens. Survival of the fittest, even between cells in the same body.

[00:01:18] Speaker B: Right. And today we're seeing that exact drama play out inside the human eye. We're looking at retinitis pigmentosa, or rp.

Now, we think of RPE as a purely genetic disease, but this paper argues that a huge part of the blindness, it's actually caused by starvation.

[00:01:36] Speaker C: It's a really crucial distinction. I mean, in rp, we've known forever that the night vision cells, the rods, they die first. That's the direct hit from the genetic mutation.

[00:01:45] Speaker B: That part makes sense. It's the first domino to fall.

[00:01:48] Speaker C: But the real mystery, and this has puzzled scientists for decades, is why do the daylight cells. The cones.

[00:01:55] Speaker B: Yeah, that's the million dollar question, isn't it?

[00:01:57] Speaker C: It is. Because most of the time, the cones are genetically fine. They don't have the mutation. They're just innocent bystanders.

[00:02:03] Speaker B: And yet, once the rods are gone, the cones follow. And that's when it becomes truly devastating. Because losing night vision is one thing, but losing your cones.

[00:02:12] Speaker C: Losing cones means losing your high acuity vision. It's losing the ability to read a book, to drive, to see someone's face. It's the loss of independence, really.

[00:02:20] Speaker B: So this paper we're diving into today proposes this theory of a metabolic heist. It suggests these innocent cone cells are Dying because their neighbors, that support staff, they just stop sharing the food.

[00:02:35] Speaker C: They're literally starving to death. And crucially, the research then asks, well, what if we can hack the metabolism of the eye to force feed these cells? Can we save daylight vision?

[00:02:45] Speaker B: It's like cellular social engineering, in a way.

[00:02:47] Speaker C: Yeah.

[00:02:48] Speaker B: So before we get into the how and science here is just incredibly cool.

We have to give credit where it's due.

[00:02:53] Speaker C: Absolutely. Today we celebrate the work of Laurel C. Chandler, Apollonia Gardner, and Constance L. Sepko.

[00:02:59] Speaker B: That's a real powerhouse team from the Department of Genetics and Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

[00:03:06] Speaker C: And this was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences PNAS on April 3, 2025.

[00:03:12] Speaker B: So, brand new science from the very top. Let's unpack this. We need to understand the crime scene before we get to the solution. We're talking about ra retinitis pigmentosa.

[00:03:20] Speaker C: Right. And just to give you a sense of the scale, RPE is the most common inherited retinal degeneration. It affects about 1 in 4,000 people.

[00:03:30] Speaker B: And the really tricky part is that it's not just one disease. Right. It's not one bad gene.

[00:03:34] Speaker C: Oh, not at all. It involves something like a hundred different genes. You could have a mutation in one, your neighbor could have one in a totally different gene.

[00:03:41] Speaker B: Which has to be a nightmare for developing treatments. You can't just make one gene therapy to fix all of them.

[00:03:47] Speaker C: Precisely. That's why finding a mechanism that applies to all of them, like this secondary death of the tones, is sort of the holy grail for retinal research.

[00:03:56] Speaker B: Okay, so let's get into this metabolic ecosystem inside the eye.

I love that term. You've got the photoreceptors, the rods and cones, and then this other layer, the.

[00:04:05] Speaker C: Rpe, the retinal pigment, epithelium.

[00:04:07] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:04:08] Speaker C: A good way to think of the RPE is as the nurse, or the feeder layer sitting right behind the retina.

[00:04:13] Speaker B: So it's the gatekeeper. Anything the retina wants to eat has to go through the RPE first.

[00:04:18] Speaker C: Exactly. So in a healthy eye, there's this really elegant symbiotic relationship. Photoreceptors are unbelievably hungry. They just devour glucose. But, and this is the key, they don't burn it efficiently. They do this thing called aerobic glycolysis.

[00:04:32] Speaker B: The Warburg effect, right?

[00:04:33] Speaker C: The very same. They eat glucose and spit out a waste product, lactate, which seems kind of.

[00:04:41] Speaker B: Wasteful, like taking one bite of an apple. And tossing the rest.

[00:04:44] Speaker C: It does seem wasteful, but it's actually part of a brilliant strategy. Because the rpe, that nurse layer, it loves lactate, it actually prefers it over glucose as its fuel.

[00:04:53] Speaker B: Oh, okay, so one cell's trash is another cell's treasure.

[00:04:56] Speaker C: Exactly. And because the RPE is so full of lactate fuel, it doesn't need the glucose coming in from the blood. It just. It spares it. It lets the glucose flow right past, straight to the photoreceptors.

[00:05:07] Speaker B: It's a perfect system. Rods and cones make lactate. The RPE eats the lactate and saves the glucose for the rods and cones.

[00:05:14] Speaker C: A perfect system until RP hits right.

[00:05:16] Speaker B: In rp, the rods start to die off.

[00:05:18] Speaker C: And you have to remember, rods are the vast majority of photoreceptors. So when they die, that massive source of lactate, the RPE's main food source, it just dries up.

[00:05:29] Speaker B: The supply chain collapses.

[00:05:31] Speaker C: It does. And the RPE gets hungry. It panics, it stops getting lactate. So it turns to the only other food available, the glucose coming from the blood.

[00:05:39] Speaker B: It raids the pantry, it goes into.

[00:05:41] Speaker C: Survival mode, starts eating the glucose itself. And the cones, who are at the.

[00:05:45] Speaker B: End of the line, they get nothing. They starve.

[00:05:48] Speaker C: That's the model. So the team at Harvard asked, can we break this cycle? Can we somehow force the RPE to be generous again?

[00:05:56] Speaker B: But how? If the rods are gone, where would the lactate come from?

[00:05:59] Speaker C: Well, there's always a tiny bit in the blood, a little from the remaining cells. But the RPE's normal transporters aren't sensitive enough to grab it.

[00:06:08] Speaker B: It's used to a fire hose, so it can't drink from a dripping tap.

[00:06:10] Speaker C: A perfect analogy. The RPE normally uses transporters called MCT1 and MC and MCT3 has what we call low affinity, meaning it's lazy. It means it needs a lot of lactate around to even bother working. Its Calamfa value is around 6 millimolar. If the concentration drops, MCC3 just shuts down.

[00:06:30] Speaker B: So it's that weak dustbuster we talked about. It just doesn't have the suction.

[00:06:33] Speaker C: Exactly. So the researchers went looking for a better tool, and they found one MCT2 monocarboxylate transporter.

[00:06:41] Speaker B: Two.

[00:06:41] Speaker C: MCT2 is a high affinity transporter. Its KM is around a 0.7 millimolar.

[00:06:46] Speaker B: Wow. So that's what, nearly 10 times more sensitive it is.

[00:06:50] Speaker C: It can suck up lactate even when there's barely any around.

So the hypothesis was, if we use gene therapy, to put this industrial vacuum MCT2 into the RPE.

[00:07:00] Speaker B: The RPE will get full on lactate again, stop eating the glucose and let.

[00:07:04] Speaker C: The glucose pass through. To save the starving cones and save vision. That was the plan.

[00:07:08] Speaker B: So how did they pull it off? This is gene therapy, right?

[00:07:10] Speaker C: They used an AAV8 Vector, which is a pretty standard virus for this kind of thing to deliver the MCC CQ2 gene. But they had to be very precise.

[00:07:18] Speaker B: You only want the support staff to get the upgrade, not the frontline workers.

[00:07:21] Speaker C: Exactly. So they use something called the best one promoter. Think of a promoter as a key.

The virus delivers the gene to all the cells, but the best one key only fits the lock on RPE cells. So the gene only turns on where they want it to.

[00:07:37] Speaker B: Clever. Precision targeting. And they tested this in a few different animal models, Right?

[00:07:42] Speaker C: A RAT model S330 forwarder and two mouse models. One albino Feb and one pigmented P23H.

[00:07:50] Speaker B: Why so many? Why not just stick to one rigor?

[00:07:53] Speaker C: You want to show it's not a fluke. Albino eyes and pigmented eyes can react differently. And rats and mice have different immune systems. If it works across the board, you know you're onto something real.

[00:08:02] Speaker B: Okay. Covering all their bases. I like it. Now, to actually see if this worked, they use some seriously cool tech.

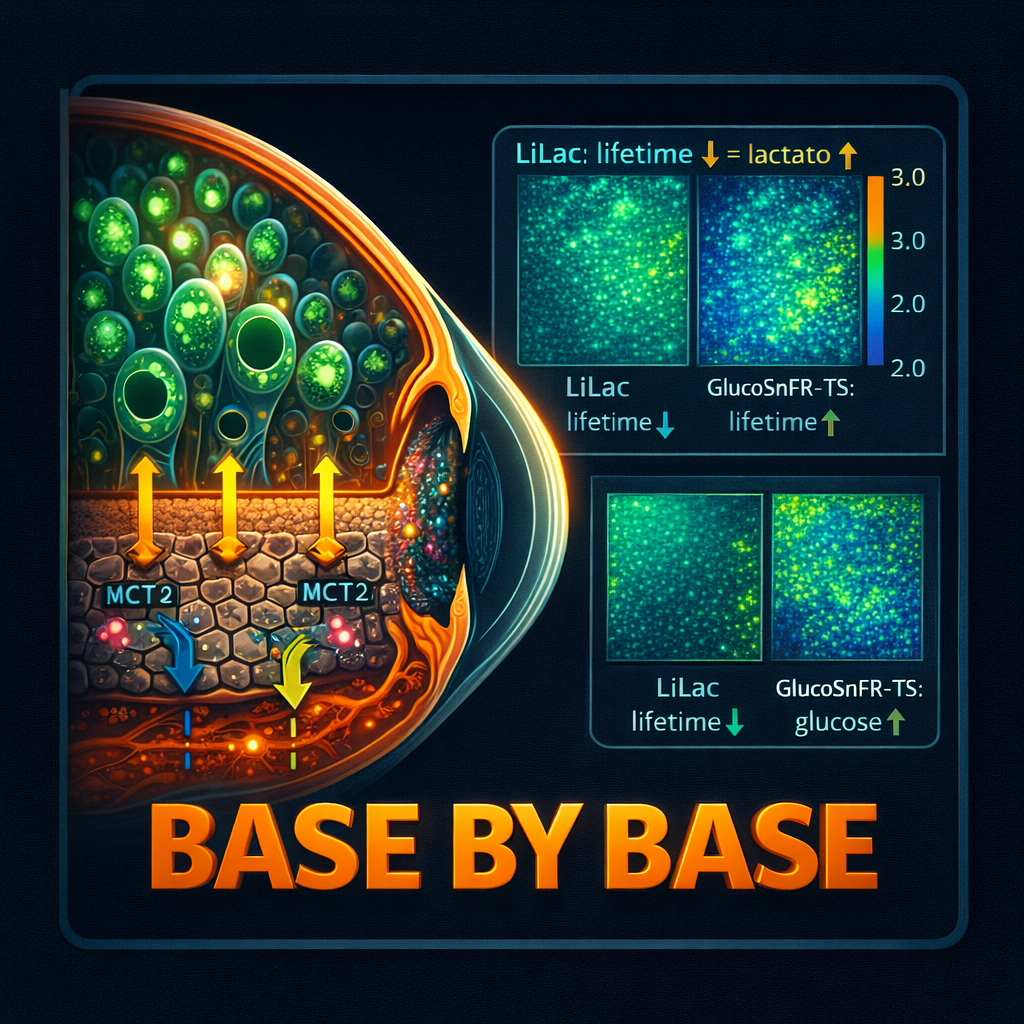

[00:08:08] Speaker C: Fluorofem.

[00:08:09] Speaker B: Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Phleem.

[00:08:13] Speaker C: Okay, break this down for me. Usually with fluorescent tags, we're just looking at how bright something glows, right?

[00:08:18] Speaker B: Intensity. But intensity can be misleading. Phleium is different. It doesn't measure how bright the glow is. It measures how long the glow lasts down to the nanosecond.

[00:08:27] Speaker C: So you're timing the glow's decay. Exactly. It's like ringing a bell. Intensity is how loud the bell is. Lifetime is how long the note hangs in the air.

[00:08:35] Speaker B: And that hang time changes depending on what the sensor is holding on to. Like lactate or glucose.

[00:08:41] Speaker C: Precisely. And that timing gives you an exact quantitative measurement of the concentration inside a living cell. It's incredible.

[00:08:49] Speaker B: It's like watching the metabolism happen in real time.

[00:08:51] Speaker C: That's exactly what it is. They used a sensor called lilac for lactate and glucosnfr for glucose.

[00:08:58] Speaker B: Glucose sniffer. I love it. Okay, so they've got the super vacuum, they've got the sensors. We. What did they find? Did the cones survive in the rats?

[00:09:05] Speaker C: Yes. A significant increase in surviving cones in the treated eyes compared to the untreated ones. Same story in the FCB mice. The untreated Eyes get these craters, these dead zones in the treated eyes. No craters.

[00:09:19] Speaker B: No craters. That's a pretty clear win.

[00:09:20] Speaker C: Yeah. And the pigmented mice also showed increased cone survival. So across three models, the structure of the retina was better preserved.

[00:09:27] Speaker B: But structure is one thing. The big question is, could the mice actually see better?

[00:09:32] Speaker C: The can they see test, they use something called the optimotor reflex, which is you put the mouse on a platform surrounded by screens showing rotating black and white stripes. If the mouse can see the stripes, its head just instinctively follows them.

[00:09:47] Speaker B: Kind of like the eye chart at the doctor's office for a mouse.

[00:09:50] Speaker C: Pretty much. And at postnatal day 40, the treated mice had significantly better visual acuity. They could see much finer stripes than the controls.

[00:10:00] Speaker B: That's amazing. They hacked the metabolism and it actually preserved vision.

[00:10:03] Speaker C: It did, but. There's always a but. By day 53, the effect faded. There wasn't a significant difference anymore.

[00:10:10] Speaker B: Oh, so it's not a permanent cure.

[00:10:12] Speaker C: It bought them time. It delayed the disease, which is still a huge deal, but it didn't stop it forever.

[00:10:17] Speaker B: Still, buying someone a few more years of sight, that's life changing. That is absolutely win, no question.

[00:10:23] Speaker C: And it proves the mechanism is sound.

[00:10:25] Speaker B: So let's go back to that Flemmin data, because they actually watched the metabolism change.

[00:10:29] Speaker C: This is the really cool part for the biochemistry nerds. The lilac sensor showed the RPE cells with MCT2 were lactate sponges. They just hoovered it up.

[00:10:37] Speaker B: So the vacuum works?

[00:10:39] Speaker C: The vacuum definitely works. But the real aha moment came from the glucose sensor. Glucosenhr.

[00:10:45] Speaker B: What did that show?

[00:10:46] Speaker C: It showed that the MCTT cells had higher levels of glucose inside them.

[00:10:50] Speaker B: Wait, hold on. Higher?

I thought the whole point was to get the glucose out to the cones. Isn't this just hoarding?

[00:10:56] Speaker C: It seems totally counterintuitive. Right, that's what I thought too, but you have to think about what it means.

[00:11:02] Speaker B: Okay, walk me through it.

[00:11:03] Speaker C: If the RPE was burning that glucose for fuel, the levels inside would be low because it's being used up.

[00:11:09] Speaker B: Right. An empty tank.

[00:11:11] Speaker C: But the tang is full. The levels are high. That means the RPE is not burning it. Why? Because it's full of lactate instead. The high lactate levels actually inhibit glycolysis.

[00:11:21] Speaker B: Ah, so the tank is full because the engine is running on a different fuel.

[00:11:25] Speaker C: You got it. And because that tank is full, there's a big pool of glucose just sitting there, ready to flow down its concentration.

[00:11:31] Speaker B: Gradient out of the RPE and to the starving cones. It's like a fully stocked pantry because the family decided to get takeout.

[00:11:39] Speaker C: That's a perfect analogy.

[00:11:40] Speaker B: Incredible. So it really validates the whole starvation theory. But you did mention some issues. Besides it being temporary, was there anything else?

[00:11:48] Speaker C: There was a little bit of a safety concern, mainly in the mice. In the rats, the RPE looked fine, but in the mice, the cells looked stressed. They were enlarged, they had these stress fibers. They just looked unhappy.

[00:12:02] Speaker B: Why the difference between rats and mice?

[00:12:05] Speaker C: It could be a lot of things. Maybe a dose issue since mouse eyes are so much smaller. Or it could be an immune system thing. There are subtle differences that could make the mouse RPE more sensitive to this kind of metabolic shift.

[00:12:17] Speaker B: Which really highlights why you test in multiple animals. If you'd only use mice, you might have abandoned the whole idea as too toxic.

[00:12:24] Speaker C: Exactly. And if you'd only used rats, you might have missed a potential safety signal. It just teaches us to be cautious moving forward.

[00:12:31] Speaker B: So, zooming out, what does this all mean? What's the really big deal here?

[00:12:35] Speaker C: The biggest takeaway by far is that this is gene agnostic.

[00:12:39] Speaker B: Remind us why that's the holy grail.

[00:12:41] Speaker C: Because RP has over 100 different genetic causes. Most gene therapies are bespoke. They're tailor made for one specific mutation.

[00:12:49] Speaker B: Which is slow, it's expensive, and it leaves people with rare mutations out in the cold.

[00:12:54] Speaker C: Exactly. But this approach, it doesn't care why your rods died. It doesn't look for the typo in your DNA. It just treats the consequence. It treats the starvation. It targets the common pathway, the common final pathway. So one treatment could, in theory, work for dozens of different types of rp. It could democratize vision therapy.

[00:13:13] Speaker B: That's the dream.

One drug, many diseases.

[00:13:17] Speaker C: And it has implications for other diseases too, like age related macular degeneration, amd, even glaucoma, where we're finding that metabolic transport is a huge issue.

[00:13:26] Speaker B: So let's wrap this up. What's the take home message?

[00:13:28] Speaker C: It's that by genetically engineering the ICE support cells to be better scavengers, we can trick them into feeding the dying light sensing cells. And it confirms that starvation is a major driver of blindness. Totally separate from the initial genetic mistake.

[00:13:43] Speaker B: A supply chain hack that saves vision.

[00:13:45] Speaker C: That's it in a nutshell.

[00:13:47] Speaker B: So here's my provocative thought to end on.

We've been talking about the eye, but the eye is essentially brain tissue, right?

[00:13:54] Speaker C: It is neural tissue, yes.

[00:13:55] Speaker B: So what could this mean for other neurodegenerative diseases?

I'm thinking about Alzheimer's or Parkinson's. You've got neurons dying and you've got support cells.

[00:14:06] Speaker C: The Goliath.

[00:14:07] Speaker B: That is the multi billion dollar question.

[00:14:09] Speaker C: If this metabolic coupling or uncoupling is the tipping point in the retina, could the support cells in the brain be starving neurons in Alzheimer's? Could we use a similar metabolic hack to save memories the way we're saving vision?

[00:14:23] Speaker B: There is a mountain of evidence growing that metabolic problems are at the heart of those diseases too. If we can apply these lessons from the eye to the brain, well, the possibilities are just staggering.

[00:14:34] Speaker C: A fascinating thought to leave you with, indeed.

[00:14:36] Speaker B: This episode was based on an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license. You can find a direct link to the paper and the license in our episode description. If you enjoyed this, follow or subscribe in your podcast app and leave a five star rating. If you'd like to support our work, use the donation link in the description.

Now. Stay with us for an original track created especially for this episode and inspired by the article you've just heard about. Thanks for listening and join us next time as we explore more science. Bass by bass.

[00:15:12] Speaker A: Night fell first and the colors thin like street lights losing oxygen and the quiet after R let go A hunger grew where we couldn't see A keeper at the border held the fuel and every bright thing learned to plead.

[00:15:37] Speaker B: But.

[00:15:37] Speaker A: There'S a river you can't erase A hidden current under the edge if you reopen what the dark ones pay the morning has a chance to wait Open the gate, let the sugar run Let the small suns keep burning on Carry the night's last heat inside so that it can stay so that it can stay alive.

Hold that signal steady and true.

[00:16:12] Speaker B: Open.

[00:16:12] Speaker A: The gate, let the light come through we drew a line where blood meets scream Wrote a new passage in the in between A fasted doorway for the tire tide so they keep us stops feeding it's on fire and in that sh the blue return Not a miracle, a measured quad you can't bring back what the dusk erase but you can change what the border takes Give it a reason to share the street and fragile sparks become a beam Open the gate, let the sugar run Let the small suns keep burning on Carry the night's last heat inside so that they can stay so that they can stay alive.

Hold that signal steady and true Open the gate, let the light come through.

In the hush of the living room sky Hear the city breathing low lines a subway pulse a harbor wind and a piano counting time if the map redraws the way we feel Then hope can be.

A defined design.

Open the gate Let the sugar run Let the small suns keep burning on Carry the night's last heat inside so that they can stay so that they can stay alive.

Oh, that? S steady and true Open the gate Let the light come through.

Let the light come through.